|

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||

|

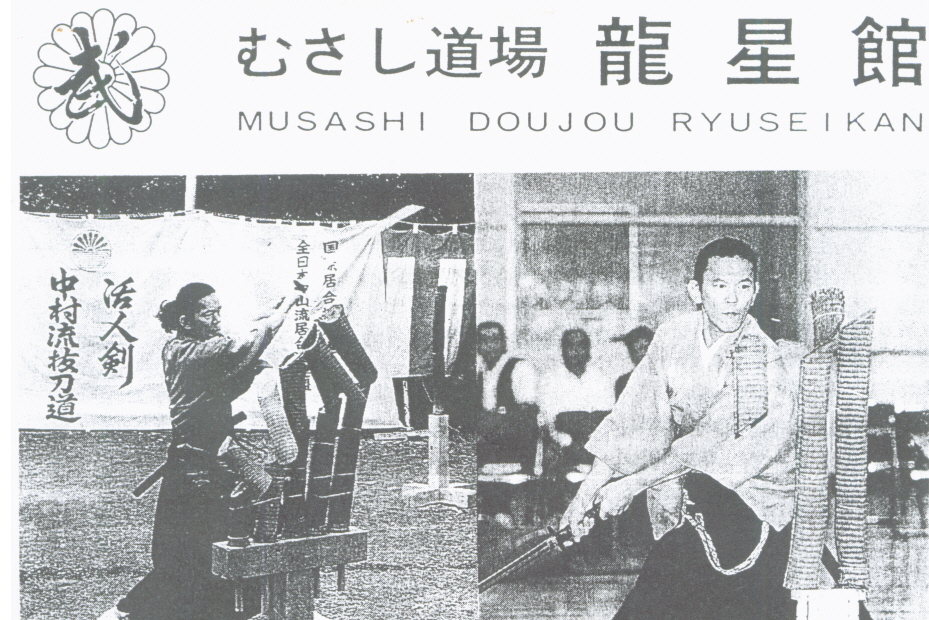

The character above is the first character in the word Bu-do” or “"Bu-jitsu"” meaning “" the way of the warrior" or the warrior arts"” in the Japanese language. Indeed, the history of the Japanese martial arts as we know them today is tied to the distinction between the two words. Both refer to the martial arts and moral code of the samurai, but the suffix of the second one ‘"jitsu"” implies an intention to use the arts for their intended purpose (combat). On the other hand, the suffix of the first word "do"” (pronounced like "dough")”) infers a higher moral concept; a way of life (the character literally means "street"”) and suggests a more benign "way"” to approach the study of martial arts. Because of this distinction, the Japanese martial arts underwent a transformation that altered the way they were practiced, and regarded, from that point on. Japan entered modem society at the turn of the century, many of the old ideas and customs from the past were being pushed aside to make room for the new. Unfortunately, the martial arts were among the things being left behind in the formation of e new modern society. In essence, people didn’t want to be connected to what was perceived as a violent, outdated, warlike mentality. This trend was single-handedly halted and reversed by the invention (or transformation) of Judo by Jigoro Kano in the year 1882. He perceived the true relevance and purpose of martial arts in modem day society; instead of a mode of combat they have become a way to better oneself. So, after studying many types of Ju-jitsu (the ancient samurai forms of combat) Professor Kano formulated Ju-do (the way of gentleness), and founded his school, the Kodokan. He implemented a color belt ranking system that is mimicked today in all types of martial arts, designed a safe way to train and compete without excessive injury, and brought Japanese martial arts back from the brink of extinction. Martial Arts once again became a noble, worthwhile endeavor that was associated with the peaceful, law-abiding, and most importantly modern society that Japan was seeking to form. Other arts soon followed suit, and gradually all of the major Japanese martial arts used the suffix “"Do"” in their names; Aiki-jujitsu_became Aiki-Do(Morihei Uebashiba, O’Sensei), various styles of Karate added the suffix “Do” and of course, Ken-Jitsu (the art of the sword) became Ken-Do (the way of the sword.) Thus, the study of the Japanese sword was kept alive and spread throughout Japan becoming a national pastime practiced widely in the public schools Kendo being mainly a sport, this left room for various schools of Iai-Do (the way of drawing the sword) to prosper teaching the ancient forms, or kata, of sword combat. The third fragment of sword study that had initially suffered from the purge of the Japanese martial arts was eventually termed Batto-jitsu, or later Batto-Do. This translates into ‘The Way of the Drawn Sword’ and generally was distinguished by continuing to do tameshigiri, or test cutting. Using a live blade, no matter what the suffix of the name of the art, still was not a very popular endeavor (a continued aversion to violence) in society at that time, so this art stayed in the background during the explosion of Japanese martial arts into modern day times. The initial reversal of this trend was accomplished by Nakamura Sensei of Toyama Ryu Batto-Do. Due to his contacts to the military, Nakamura Sensei was able to teach many people and spread Batto-Do all over Japan, and abroad. Other sensei have now taken the forefront in proliferating and improving the arts of sword study, and chief among them is none other than Mitsuhiro Saruta, Soke (inheritor) and Director of Ryuseiken Batto-Do. Mitsuhiro Saruta, Sake (or founder/inheritor) of Ryuseiken Batto-Do, was born in Hiroshima Japan and soon began studying Kendo at the age of six years old. Kendo is a sport played both in schools and in clubs using a bamboo representation of the sword (called shinai), head, wrist, and body armor, and a point scoring system involving strikes to those three areas. Saruta Sensei quickly mastered this game, competing throughout his schooling, and soon moved on to studying various styles of laido (these styles preserve many of the old forms and positions of sword combat passed down from generation to generation). laido customarily only uses unsharpened swords or wooden ones to practice forms, so after studying these arts he was ready to encounter Batto-Do (the way of the drawn sword). He initially experimented with test cutting on his own, but soon met Nakamura, Sake of Toyama Ryu Batto-Do at a demonstration. Nakamura Sensei was so impressed with Saruta Senseis cutting ability he offered to teach him and work together to bring Batto-Do to the public. For several years, Saruta Sensei worked with and learned from Nakamura Sensei, puffing in place the last element that he needed to reunite the three areas of sword study; kendo (sword combat), kata (forms), and tameshigiri (test cutting). In the late eighties he formulated his own, all inclusive style of sword study calling it Ryuseiken (Dragon Star Sword) Batto-Do. He began teaching this system at a dojo shared by him and his brother called Musashi Dojo in Sakai City, This is where I met Saruta Sensei in 1995 and began my study of Ryuseiken Batto-Do. During my time there I watched Ryuseiken grow incredibly in membership and affiliations due solely to Saruta Sensei’s tireless efforts. He now has students all over Japan, and indeed, all over the wand. There are dojos in the Phillipines, Seoul, Korea, and the United States. Just before leaving in the year 2000, I was privileged to attend the official dojo opening ceremony for Saruta Senseis brand new, beautifully built dojo back in his hometown of Hiroshima, Japan. Saruta Sensei continues to teach today both at home and abroad. |

|||||

|

| [Home] [History] [FAQ's] [Anatomy PT 1] [Anatomy PT 2] [Terminology] [Esoteric Principles] [Test Cuts] |